Best Practices For Ship’s Junior Officers On Their First Voyage

The rank of a junior officer on ships has become commonplace with a lot of shipping companies recently. The gateway to having full officer on watch (OOW) rights on a vessel, this rank is between obtaining the 2MFG license and that of Third Mate.

The time as a Junior Officer on a ship is a time to learn the duties and responsibilities of the Third Mate, which actually might help enhance the knowledge of cadets in their quest to become an OOW.

As with the time as a cadet or trainee, the primary focus of the Junior Officer is to learn and enable oneself to become worthy of becoming a capable OOW, competent enough to carry out the navigational watch solely. While it might hinder some seeing as the salary is usually significantly lower than that of a Third Mate, there isn’t much of an option nowadays for fresh Third Mates to choose from. It is suggested that if one’s parent company requires the rite of passage as a Junior Officer, one should take it.

Time spent as a cadet expecting the other officers to teach you has obviously not always been as expected and naturally so – everyone has too much on their plate; the Junior Officer rank is the time to ensure that all doubts are cleared! Keeping that in mind, the following are some pointers to the best practices applicable to Junior Officers on their first voyage:

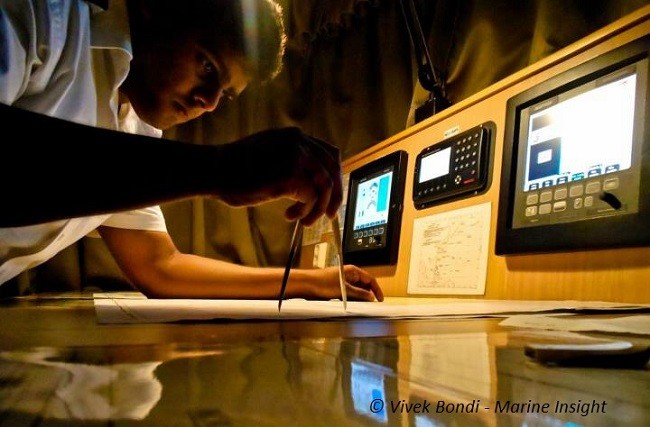

Navigation: Most junior deck officers do their watch as per the Third Mate’s designated slot of 0800-1200 and 2000-0000 hours. Keeping watch as an extra hand as a Cadet is different to that as a junior officer. Essentially, one has to take it as one would do as a Third Mate and therefore utmost diligence is obvious. While as a cadet, the chief officer was the go-to person for navigation-related doubt, in this case, troubleshooting ought to be done by self.

Publications: Third Mates have to do part of the corrections with the Second Mate, such as for the ALLS. Cadetship might have been about seeing how the Third Mate did it. In the case of a JO, it’s expected to DO on own. This is applicable to all other ancillary work on the bridge (such as port papers, muster lists, drill records etc). The junior officer should do all of that work, reducing the load on the Third Mate and thereby of all other officers. As a cadet one might be an extra hand, a trainee; a JO is essentially already a Third Mate in a learning phase.

Life-Saving Appliances (LSA): Knowing how to refill compressed air in the cylinders, making a requisition, drawing up the right paperwork for port maintenance of equipment etc. are expected of a JO. Cadetship might have demanded a lot of time on deck; this is the ideal time to learn the above aspects thoroughly. Add to this the regular maintenance of the lifeboat, life raft and the lifebuoys- checking expiry of the rations, ensuring upkeep and cleanliness- jobs that are obvious to the rank of a Third Mate.

Fire Fighting Appliances (FFA): Derusting the fire line, maintenance of the portable extinguishers, their location, ensuring the fire plan is in the right place- basically sharing all of the Third Mate’s workload seeing as it’s only a few months of experience leading to the rank of OOW.

Pilotage: Time as a cadet during pilotage is spent on mooring operations and rightfully so. It’s important to know the ropes before commanding their operation. As a JO, more time is freed up to actually do the control tests as well to be on the bridge during pilotage in order to relay and execute orders from the Master. Even if this is done as a cadet, it’s mostly about standing around and making coffee then!

Port Work: Most of the cadetship is about taking soundings! As a junior officer, assuming responsibility to undertake the port watch, entirely relieves a lot of the officers and also preps one for the times to come to do the same as a Third Mate. Basic jobs such as tending to moorings, rounds on deck, recording cargo operations – jobs that are not normally assigned to cadets – are expected to be carried out in this phase.

Miscellaneous Work: While most work is specifically assigned as per rank, we have often noticed that it’s never limited to the assigned work. While cadetship might not have left much time to do these other jobs, as a junior officer one must learn the extra bits that would be eventually needed in the future. Bond-related work, stores, spares, rations etc. might seem like easy work but they do require perfection over time. Additionally, to do justice to the 2MFG license, it’s also advised to pick up some skills from the Second Mate if there is time to spare. Having more knowledge only makes one a better officer.

It’s best to kick the notion that some have of a junior officer being a glorified cadet. Instead, the JO is actually a Third Mate waiting to become one. There is no cap on practical competency, and the more knowledge one acquires the better Officer one can become. The rank of a Junior Officer actually gives one time to brush up on the aspects that need polishing since the 2MFG exams take away the significant time between the last time sailed and the current. If used to the full potential, this time can reap a multitude of benefits for the expecting OOW.

Disclaimer: The authors’ views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of Marine Insight. Data and charts, if used, in the article have been sourced from available information and have not been authenticated by any statutory authority. The author and Marine Insight do not claim it to be accurate nor accept any responsibility for the same. The views constitute only the opinions and do not constitute any guidelines or recommendation on any course of action to be followed by the reader.

The article or images cannot be reproduced, copied, shared or used in any form without the permission of the author and Marine Insight.

Latest Shipboard Guidelines Articles You Would Like:

Do you have info to share with us ? Suggest a correction

About Author

Shilavadra Bhattacharjee is a shipbroker with a background in commercial operations after having sailed onboard as a Third Officer. His interests primarily lie in the energy sector, books and travelling.

Subscribe To Our Newsletters

By subscribing, you agree to our Privacy Policy and may receive occasional deal communications; you can unsubscribe anytime.

Web Stories

An interesting and sensible article. For comparison’s sake here’s how it worked when I went to sea in 1948. I signed an Apprentice’s Indentures for four years with a UK shipping company at about £30 a year. The first two years I worked with the crew doing the variety of jobs laid down by the Company to ensure that I “knew” the ships. Evenings and weekends we were taught navigation by the Chief and Second mates. The third year was spent working as a Junior officer, much as described in the article above, assisting the watch keeping mates and any specialised jobs considered too technical for the crew. Often keeping watch alone if the duty officer was “otherwise” engaged.

At the end of the third year my indentures were cancelled by mutual consent and I became an “Uncertificated” Third Mate keeping the 8-12 am/pm watch and on an enhanced rate of pay. This pay came in useful supporting me when I went to college later. By this time I could recite the IRPCS by heart. As an aside, in those years shortly after the end of WW2 alcoholism amongst many senior officers was rife. Because of this keeping watch was a serious responsibility, as calling for any assistance was often a waste of time! It certainly concentrated the mind. In spite of that it felt good to be in full charge of the watch. Contemporaries could relate similar experiences.

[Years later I realised that one of the reasons for alcholism was that many of these men were suffering from PTSD from years of wartime stress. (Read The Battle of the Atlantic: By Jonathan Dimbleby.)]

At the end of the fourth year I went to college for six months to refresh the theories before taking and passing my Second Mates Ticket. I returned to sea as a Second Mate. During the four years I probably had no more than a couple of months home leave each year.

These conditions wouldn’t work nowadays, but the length of sea-time was very good preparation, none of my apprentice shipmates, as far as I can remember, ever failed their certificates and all got their Master’s COC Unlimited within ten years of going to sea. Mentoring was critical and self-learning required discipline. Sufficient mentoring appears to be a problem these days. From my armchair readings many cargo ships now have insufficient crew numbers to deal with modern regulations, paperwork and a variety of inspections. Modern technology is an aid but it all adds work and a requirement of knowledge that doesn’t happen on its own. GMDSS, ECDIS, and all the other courses required by STCW have become a time and financial burden.